Decisión preliminar: Certificación del proyecto de la presa de Ma'an, pendiente de LIHI #207-I

11 de diciembre de 2025Decisión final – Certificación del Proyecto del Centro Rutland, VT

7 de enero de 2026Bajo impacto vs. Sin impacto: La verdad de la misión de LIHI en acción

Hace unas semanas, me desperté con docenas de notificaciones en redes sociales. Como gerente de comunicaciones del Instituto de Energía Hidroeléctrica de Bajo Impacto, esto no es inusual, pero el tono era diferente esta vez. Una publicación viral afirmaba que LIHI estaba considerando certificar un proyecto inmerecido. Algunas publicaciones incluso nos acusaron directamente de lavado de imagen, una práctica engañosa de presentar una empresa o producto como ecológico como estrategia de marketing. Para la hora del almuerzo, la publicación ya había cobrado fuerza y había recibido algunos mensajes de partes interesadas, asesores y otras personas preguntándonos si debíamos emitir una declaración.

Momento de transparencia: no era la primera vez que LIHI recibía críticas públicas. Y dado el contexto en el que trabajamos, probablemente no será la última. Pero esta vez, me inspiró a compartir lo que hacemos como organización de una manera diferente.

Esto es lo que desearía que nuestros críticos entendieran. Esto es lo que desearía poder decirles a periodistas, defensores del medio ambiente escépticos de nuestro programa de certificación y a toda persona que realmente quiera saber si estamos marcando la diferencia o si somos simplemente otra organización que se esconde tras la jerga y las palabras clave de la industria. Así que aquí va: lo bueno, lo malo, lo feo y lo esperanzador.

La verdad incómoda

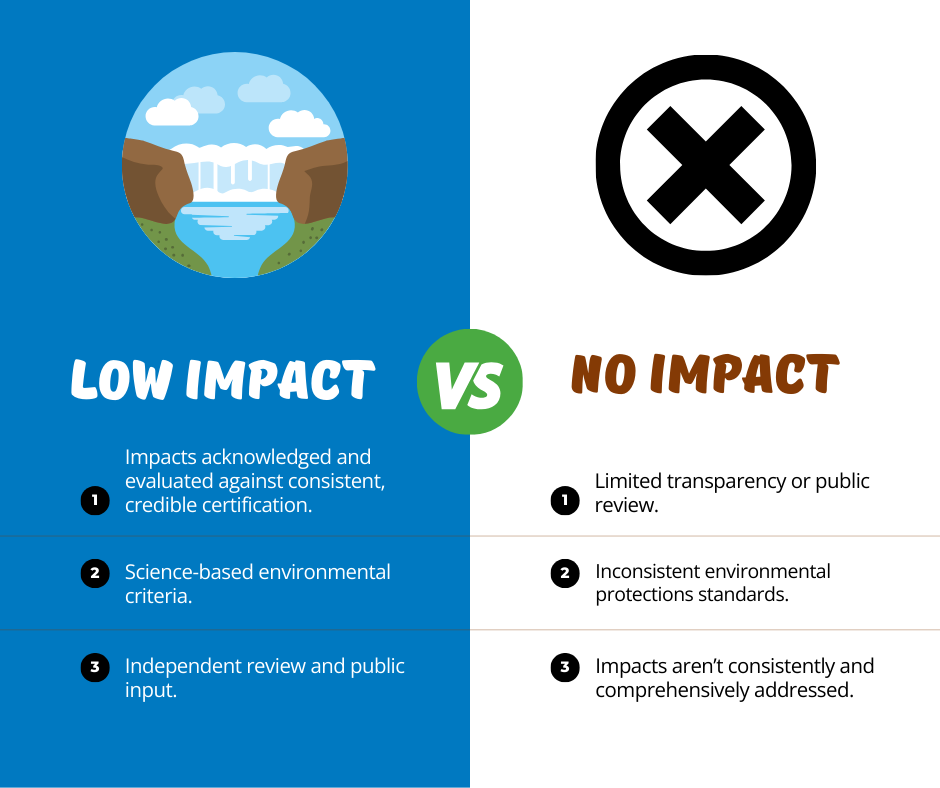

Empecemos con algo que podría sorprenderle: no existe la energía hidroeléctrica, solar ni eólica de impacto cero. Toda forma de generación de energía, renovable o no, afecta al medio ambiente y a las comunidades que la rodean.

La fabricación de paneles solares requiere la extracción de minerales de tierras raras, operaciones que pueden afectar el paisaje y consumir enormes cantidades de agua. Las turbinas eólicas pueden matar aves y, a menudo, generar ruido de baja frecuencia que afecta a los residentes cercanos. Y la energía hidroeléctrica —la fuente de energía renovable de la que la humanidad ha dependido durante siglos— puede alterar los ecosistemas fluviales, afectar a las poblaciones de peces y modificar el caudal del agua.

Cuando se constituyó LIHI en 1999, los fundadores de la organización comprendieron que las presas hidroeléctricas no son solo infraestructura, sino que están entretejidas en la estructura de las comunidades. Estas instalaciones pueden proporcionar energía renovable de carga base para hospitales y escuelas. Pueden respaldar las bases impositivas locales que financian los departamentos de bomberos y el mantenimiento de carreteras. En las zonas rurales, han sido una fuente de empleo para generaciones de familias que han operado las mismas instalaciones durante décadas. En las ciudades, la energía hidroeléctrica puede proporcionar energía renovable confiable que hace posibles los ambiciosos compromisos climáticos. Los fundadores de LIHI comprendieron que pedir la eliminación total de las presas no era realista ni necesariamente deseable. En cambio, se plantearon una pregunta diferente: si estas presas van a seguir operando, ¿cómo garantizamos que lo hagan de manera responsable? Ese enfoque pragmático —reconocer el papel legítimo que desempeña la energía hidroeléctrica en las comunidades al tiempo que insistimos en estándares ambientales significativos— es lo que llevó a la organización a adoptar la postura de "bajo impacto".“

Si bien el nombre del Instituto de Energía Hidroeléctrica de Bajo Impacto es, sin duda, un nombre complejo, su misión queda claramente establecida. El uso de "bajo impacto" se eligió deliberadamente como una modificación honesta que reconoce la existencia del impacto, a la vez que se compromete a minimizarlo. Establece expectativas realistas de que, si bien las instalaciones pueden afectar los ecosistemas fluviales y los patrones naturales de flujo, también podemos reducir significativamente dichos impactos mediante prácticas operativas con base científica, la participación significativa de las partes interesadas y el monitoreo continuo.

El uso de la palabra “impacto” también es intencional, ya que dedicamos un esfuerzo considerable a documentar exactamente cuáles son esos impactos y cómo los están abordando las instalaciones.

LIHI no promete lo imposible; definimos un estándar alcanzable que demuestra mejoras ambientales mensurables. Al trabajar en la intersección de las operaciones hidroeléctricas y la defensa del medio ambiente, impulsamos un debate que a menudo se olvida en medio de la controversia en torno a las energías renovables.

Un proceso probado que cumple la promesa

En un mundo ideal, todas las instalaciones hidroeléctricas serían calificadas como de bajo impacto, pero esa no es la realidad en la que vivimos.

Cuando una instalación solicita la certificación, nuestro equipo se reúne internamente para determinar cómo las operaciones del proyecto se alinean con nuestra criterios del programaa. Revisores externos cualificados analizan las solicitudes con más detalle antes de compartirlas con el público para recibir comentarios. El período de comentarios públicos tiene una duración mínima de 60 días, durante los cuales se anima a grupos ambientalistas, naciones tribales, agencias de recursos y comunidades locales a compartir sus inquietudes, perspectivas y comentarios generales.

Una vez finalizado el período de comentarios públicos, nuestro equipo revisa todas las aportaciones y las publica en un informe completo. Todas nuestras decisiones de certificación están disponibles públicamente en nuestro sitio web. Las solicitudes, los comentarios de las partes interesadas, las condiciones que imponemos y los requisitos de supervisión: todo está disponible.

Nuestros estándares fueron desarrollados y se revisan periódicamente con base en investigaciones basadas en la ciencia y discusiones con grupos ambientales y tribales, operadores de energía hidroeléctrica y agencias reguladoras, lo que da como resultado criterios de programas de certificación que definen de manera integral lo que califica a un proyecto como de “bajo impacto”.”

Algunas solicitudes de instalaciones cumplen nuestros estándares a la perfección; otras reciben condiciones para mejorar los resultados; y otras se retiran porque no pueden cumplir nuestros estándares, no quieren cumplir con las condiciones propuestas o no encuentran un incentivo financiero para hacerlo. Pero quienes consideran nuestras recomendaciones y realizan mejoras son quienes realmente realizan el trabajo de la misión.

Por ejemplo, en 2015, Energía renovable de Eagle Creek firmó un memorando de entendimiento sobre licencias para la venta de alcohol con el Servicio de Pesca y Vida Silvestre de EE. UU. para cumplir con las disposiciones de certificación. El acuerdo estipula el monitoreo de caudales mínimos para cuatro de sus proyectos en New Hampshire (LIHI). #177, #118, #120, y #123), incluidos los cronogramas de implementación del paso de peces y las protecciones para los murciélagos orejudos del norte.

La brecha de rendición de cuentas de la que nadie habla

¿Estás listo para otra cruda verdad?

Sin LIHI, las centrales hidroeléctricas seguirían funcionando. Claro, seguirían sujetas a regulaciones federales y estatales: las licencias de la Comisión Federal Reguladora de Energía, las certificaciones estatales de calidad del agua y las consultas sobre la Ley de Especies en Peligro de Extinción. Esas regulaciones son importantes, y no las reemplazamos. Las complementamos.

Aun así, el cumplimiento normativo suele ser mínimo indispensable y, con frecuencia, insuficiente para fomentar la gestión ambiental. Además, algunos proyectos están exentos de la FERC y carecen de una supervisión sólida más allá de su autorización inicial, que en algunos casos se emitió hace 50 años. La heterogeneidad en la supervisión implica que los cambios en las condiciones externas no siempre impulsan cambios operativos. Aquí es donde interviene LIHI.

Las instalaciones que desean obtener la certificación deben demostrar que cumplen con los rigurosos estándares de desempeño ambiental y social de LIHI, lo que a menudo implica superar los mínimos regulatorios. Deben interactuar activamente con las partes interesadas. Deben presentar verificaciones de cumplimiento anualmente y recertificarse cada 10 años, lo que significa que las certificaciones no son estáticas; evolucionan a medida que cambian las circunstancias sobre el terreno.

Hemos visto instalaciones modificar sus operaciones para beneficiar el paso de peces río abajo y negociar acuerdos que han mejorado la comunicación y las relaciones con las comunidades circundantes.

¿Podríamos hacer más? ¿Podríamos ser más rigurosos con nuestros estándares? Es posible, y trabajamos constantemente para lograrlo. ¿Existen críticas legítimas sobre decisiones de certificación específicas? A veces sí, y nuestro equipo y el consejo de administración las toman en serio.

Aunque comprendo a los escépticos sobre nuestra misión y posicionamiento, los reto a considerar lo siguiente: ¿qué pasaría si no existiera un LIHI? ¿Cuál sería la alternativa? ¿Y cómo se vería eso para los ecosistemas y las comunidades de todo el país?

Abordando la transición energética en tiempo real

Nos encontramos en medio de una transición energética que requerirá concesiones difíciles. Lo cierto es que la demanda mundial de electricidad está creciendo y el cambio climático nos exige eliminar gradualmente los combustibles fósiles. Necesitamos energía renovable, mucha, y que se despliegue rápidamente. Pero toda forma de energía renovable afecta a los paisajes, los ecosistemas y las comunidades. Los parques solares consumen tierras que podrían ser hábitat o tierras de cultivo. Los parques eólicos alteran los horizontes y las rutas migratorias. La energía hidroeléctrica transforma los ríos.

Estas no son razones para dejar de construir energías renovables. Son razones para construirlas y ubicarlas de forma responsable, con transparencia sobre los impactos y esfuerzos genuinos para evitar y minimizar los daños, o, mejor aún, para mejorar el statu quo. LIHI existe porque creemos que la industria hidroeléctrica puede y debe superar los mínimos regulatorios. Creemos que las partes interesadas merecen tener voz en el funcionamiento de las instalaciones. Creemos que la transparencia y la rendición de cuentas mejoran los resultados. Y creemos que la mejora continua, no la perfección, es el objetivo realista.

No todos estarán satisfechos con esa respuesta. Para algunos, la energía hidroeléctrica es irremediablemente perjudicial. Otros afirmarán que las instalaciones certificadas no tienen ningún impacto ambiental positivo. Sin embargo, nuestro proceso documentado ha demostrado mejorar la transparencia, la participación pública y la rendición de cuentas. El proceso crea incentivos para la mejora, plataformas para la participación de las partes interesadas y la rendición de cuentas pública. ¿Es perfecto? No. ¿Es mejor que la alternativa? Sí.

Nuestro trabajo es desordenado, imperfecto y, a veces, ingrato, pero es necesario y está mejorando gradualmente la industria.

Si ha leído hasta aquí, podemos asumir que le preocupa el funcionamiento de las centrales hidroeléctricas en su cuenca, y lo invitamos a participar en nuestro próximo período de comentarios públicos. Usted tiene voz en el proceso que fortalece nuestros estándares y hace que nuestro programa sea más eficaz; lo animo a que la use porque queremos saber su opinión.

Para obtener actualizaciones y anuncios sobre la certificación de proyectos en su estado, haga clic en aquí para suscribirse a la lista de correo electrónico de LIHI.

_____

Whitney Stovall es Gerente de Comunicaciones del Instituto de Energía Hidroeléctrica de Bajo Impacto. Las opiniones expresadas en este artículo son suyas y reflejan su conocimiento y experiencia en la gestión de la percepción pública y la participación de las partes interesadas en el sector de las energías renovables.